Literacy. It is the foundation of American Public Schools, and an important arc in the story of democracy. But what does literacy really mean, especially in a modern, digital world?

Definitions

This is the Miriam Webster definition of literacy:

Being educated, cultured; able to read and write; versed in literature or creative writing; lucid, polished; having knowledge or competence.

But when you boil it down, the generic definition of literacy is the ability to read, write, and perform math so that you can function in your society. That’s why in the United States, children are required to attend school and obtain a high school diploma. Graduating from high school (or passing a GED [General Educational Development] test) is the measure to prove basic adult literacy.

But is literacy simply the ability to read, write, and do math? Do you just need to read the words that are put in front of you? Do you need to be able to regurgitate what you read into written words, or do you need to be able write your own thoughts? And does this include the ability to evaluate the validity of the information that you consume?

Applications of Literacy

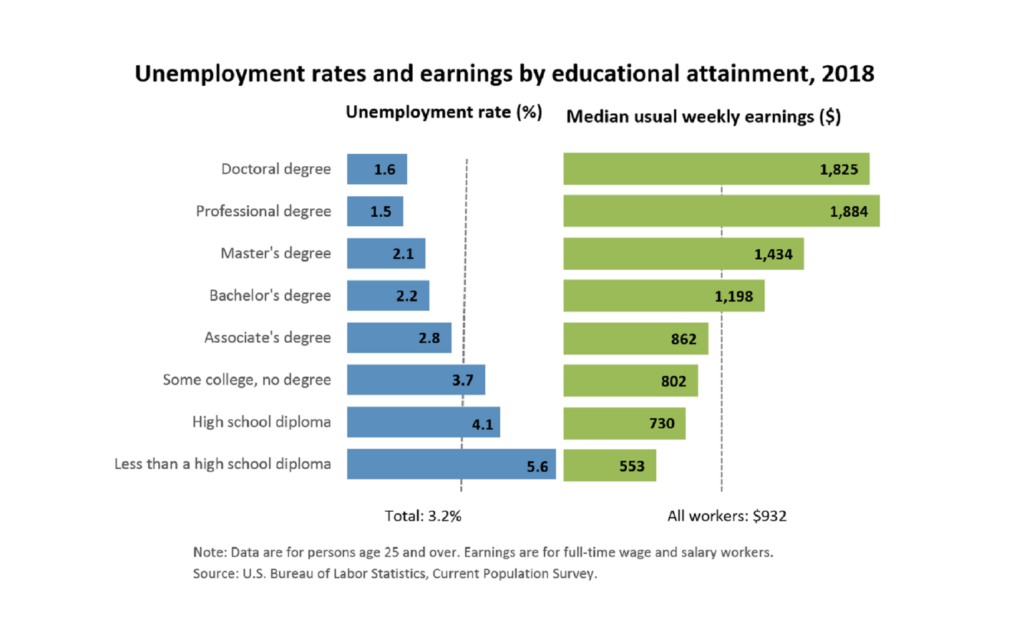

Literacy is important, as it seems to be an indicator for societal success. For example, this chart from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that you can earn more money the more education you have. This chart seems to reinforce that the true meaning of literacy is the ability to read, write, and perform math so that you can function in your society.

But there’s a dark side. Literacy opens doors financial security and the ability to function as equals in a democratic society. Literacy tests were used in the 1800s to prevent Irish immigrants from voting, and then again in the Jim Crowe era, denying black voters their right to vote. These citizens were given 10 minutes to take tests like this, and 1 wrong answer meant you wouldn’t be registered to vote. There are several ways to interpret each question, meaning if the voting registrar didn’t want you on the rolls, you weren’t going to be on the rolls. For interesting 1st person accounts of this, visit this site.

Media Literacy

As technology improved, there became more ways to consume information that reading printed words, and more ways to transmit information than writing words. There had to be different ways to describe proficiency with all types of media. This is how the National Association for Media Literacy defines media literacy:

Media literacy is the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, create, and act using all forms of communication. In its simplest terms, media literacy builds upon the foundation of traditional literacy and offers new forms of reading and writing. Media literacy empowers people to be critical thinkers and makers, effective communicators and active citizens (emphasis mine).

Part of the definition – being critical thinkers and makers – is important when it is easy to create persuasive content. How can you tell the information you’re consuming is real, that it’s not trying to trick you into believing something else? How can you be sure it’s not propaganda?

Media Evaluation: How to Tell If Content Is Useful or Propaganda?

The original meaning of the word propaganda came from a committee of cardinals established in 1622 by Pope Gregory XV named Congregatio de Propaganda Fide, or “congregation for propagating the faith”. The goal of this group was to promote Catholicism in non-Catholic countries. By 1790, propaganda meant “any movement to propagate some practice or ideology”. (via) But after WWI’s large-scale propaganda, the word took on a negative connotation.

The Institute for Propaganda Analysis (IPA) was founded in 1937 to do something about the fascism propaganda that was beginning to be shared with new technologies (radio broadcasts, film, etc.), hoping to provide citizens the information they needed to avoid being duped by misinformation. They believed that education was the American way to deal with disinformation.

Digital Literacy

Now we come to the electronic age, and we need to update the literacy definition again to account for the new ways to consume and create information. The American Library Association defines digital literacy this way:

Digital literacy is the ability to use information and communication technologies to find, evaluate, create, and communicate information, requiring both cognitive and technical skills (emphasis mine).

Evaluate takes on a more important meaning in this case. With media literacy, you know who gives you a pamphlet, or who placed a print ad in a newspaper. But how do you figure out how content is put into the feeds of applications you use? How do you know who is creating the information that you are consuming via algorithms in your feed, and how that information got there in the first place?

I think the IPA had it right. The only way to combat misinformation, propaganda, fake news, whatever you want to call it, is to educate ourselves on how it gets into our feeds, and how to distinguish it from non-propaganda. We need to become digitally literate, and we need to make sure are family and friends are digitally literate as well. That’s why I started Digital Sunshine Solutions.

Please subscribe to our RSS feed or follow us on LinkedIn for more information on how to help with this.

3 thoughts on “Does Literacy Matter in a Digital World?”